The Beat Goes On: More Evidence Against Ultra-Processed Foods

And three food stories that grabbed us this week

Two years ago, I hadn’t heard the term “ultra-processed food,” but since then it has invaded the wellness discourse with a speed and intensity that’s impressive even by health fad standards. There exists now a widespread suspicion that UPFs — items ranging from snack bars to frozen entrees, with their lengthy ingredient lists of modified starches, refined oils, preservatives, humectants, and so on — are the root of all dietary evil, not just responsible for the global obesity epidemic but also a risk factor for various cancers, heart disease, diabetes, and depression.

What’s more, this backlash against UPFs is now shockingly broad-based. It’s not just granola-eating liberals! RFK Jr.’s Make America Healthy Again platform has somehow united Republicans — whose historical nutrition achievements include classifying pizza as a vegetable and ensuring that there is no limit on starchy potatoes in school lunches — with the Michael Pollan crowd. They’re all now pounding the table for increased regulation of the marketing and sale of UPFs.

Not to sound like a Cheetos apologist, but: What’s still missing from the conversation is robust data supporting these claims. Sure, it feels right that cheap, industrial, additive-laden food should turn out to be a Very Bad Thing, but the actual linkages between consuming these foods and negative health outcomes are still nascent, and some of the evidence to date is contradictory or inconclusive. Sorry, but it’s true!

This may well be because we haven’t been researching the question for long enough. The earliest studies investigating the health impacts of eating ultra-processed foods versus less-processed ones are only about five years old. That’s when a National Institutes of Health (NIH) researcher named Kevin Hall released the results of a randomized controlled trial, now PubMed famous, comparing calorie consumption and weight gain on a diet high in UPFs versus one centered on minimally-processed foods.

Hall had a group of 20 volunteers live at an NIH facility for four weeks, during which time all their meals were controlled and biometrics measured. This is a very fancy and very rare breed of nutrition study; most rely on people reporting what they eat after the fact, and as we all know from experience, people often misremember what they ate … or lie to make themselves look good.

The two diets in Hall’s study matched in their nutritional content, meaning they had the same concentrations of fat, sugar, salt, fiber, protein, and so on, such that the only variable was how much processing the foods had undergone.

The result of that study? Participants on the ultra-processed diet ate an average of 500 more calories per day than did the minimally processed group. That’s a huge effect.

Now Hall is back with early data from a new, much-anticipated follow-up study, and the results are pretty juicy. He presented some initial findings last month at a conference at University College London, and then teased them last week on X.

Hall’s new study also took place over four weeks, and included a few dozen participants living as inpatients at an NIH facility. This time, instead of two diet groups, Hall and his team divided the subjects among four diets:

Minimally processed, low in energy density and low in hyper-palatable foods (MPF ll)

Ultra-processed, high in energy density & high in hyper-palatable foods (UPF hh)

Ultra-processed, high in energy density & low in hyper-palatable foods (UPF hl)

Ultra-processed, low in energy density & low in hyper-palatable foods (UPF ll)

Dizzying, I know. “Energy density” refers to the average number of calories per gram in the foods served; peanut butter and Snickers bars are energy dense, watermelon and canned minestrone soup are not. Hall doesn’t define “hyper-palatable” in his talk, but imagine foods that are perfectly calibrated to be irresistible, like Oreos and Popchips.

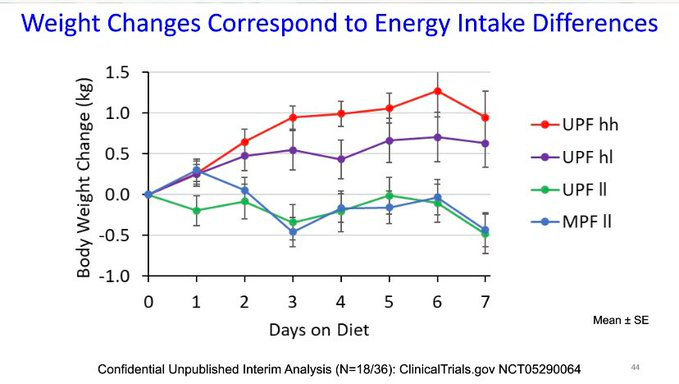

The big headline from Hall’s talk was that participants on the energy-dense, hyper-palatable diet (red bar, below) ate 1,000 more calories a day than those on the minimally-processed diet (blue bar). A thousand calories! This despite the fact that all groups ate at the same rate and reported the same level of fullness and satisfaction from their meals. An even larger effect than in the first study.

I’ll say again that this is based on a very small study group; at this point, the data represent just 18 participants. But Hall’s findings certainly suggest that people need to eat a lot more Lunchables or Cap’n Crunch to feel as satisfied as they would by, say, a turkey sandwich or a bowl of oatmeal. As Marion Nestle summed it up in a recent Food Politics post: “We love and cannot stop eating yummy high-calorie foods.”

Perhaps even more interesting, in my opinion, is the comparison between the minimally-processed diet group and the group that ate UPFs that were less energy dense, and not quite as irresistible (green bar, above). Those groups consumed nearly the same number of calories.

As you can see from the blue and green lines in the graph below, the two groups also lost roughly the same amount of weight over the course of a week. If the core problem with UPFs was truly their very nature as highly processed substances, you’d expect that difference between ultra-processed foods of any type and minimally processed ones to be larger. Perhaps this is a distinction without a difference — aren’t most ultra-processed foods calorie-dense and irresistible? — but still, it’s worth noting that how much the participants ate, and how much weight they gained, varied substantially based on exactly which UPFs they were consuming.

Hall’s team is only halfway through crunching data from this study — he says full results are expected in mid-2025 — and there’s a lot we still don’t know based on his teaser. Will the results stay the same when the full group has been analyzed? What, exactly, counts as a “less hyper-palatable” ultra-processed food? But for now, the findings certainly seem to point to the idea that it’s not the processing, per se, that’s the issue — it’s eating food that’s calorie-dense and engineered to be irresistible.

What We’re Reading

How Honeycrisp Apples Went from Marvel to Mediocre / Serious Eats

It’s almost hard to remember the days when there were at most three types of apples at the grocery store: Red Delicious, Yellow Delicious, and Granny Smith. The Honeycrisp changed all that, proving that (actually) delicious fruit would sell more than a perfect-looking apple named “delicious.” But over the last 15 years, Honeycrisps have become less tasty. Serious Eats tells the fascinating story of how industry greed spoiled America’s “it” apple.

Chocolate Prices Are Rising. Does Science Have a Solution? / Wired

Cocoa prices reached record highs this year, as difficult weather and disease tamped down production. But scientists in Switzerland have developed a way to use not just the cacao beans but also the pulp and surrounding “endocarp” to make chocolate, with the goal of increasing farmers’ revenue and allowing them to expand. But will it taste like chocolate?

Taxing Farm Animals’ Farts and Burps. Denmark Gives It a Try. / New York Times

Globally, the food system accounts for a fourth of greenhouse gases, and a big chunk of that comes from animal agriculture. And so, starting in 2030, Denmark will tax farmers for every ton of carbon dioxide equivalent that their operations produce. Perhaps not surprisingly, Danish farmers are taking it on the chin. “They understand they need to do it; they want to do it,” Peder Tuborgh, CEO of Europe’s largest dairy cooperative, told the Times. “They know it is protecting their reputation, and they’re still producing.”