I Tested Yuka, the Wildly Popular Grocery App

It’s got issues, but there's a new – and better – alternative

Hi readers! Lots of you sent me the Wall Street Journal story that ran a couple of weeks ago about Yuka, the food and cosmetics scanning app, asking what I thought about it.

Yuka is the creation of a French tech startup, has over 65 million users across 12 countries, and is currently among the top free apps in the “health & fitness” category in the App Store. Many of my friends swear by it as a way of choosing products at the grocery store. Me? I’ve got my doubts.

For the uninitiated, here’s what Yuka offers: When you scan the barcode of a food product with your smartphone (or search for it by name in the app), a score card pops up, providing information about what additives the product contains, as well as how much saturated fat, calories, sugar, protein, fiber, and sodium. Yuka’s algorithm crunches all that information into a score ranging from 1 to 100, plus a corresponding traffic light rating that goes from bad (red) to poor (orange), good (light green), or excellent (dark green).

It’s unsurprising that Yuka is wildly popular today. Once you depart from the perimeter of the grocery store, sussing out what to buy and whether or not it’s good for you starts to feel incredibly complicated. Consumers have never been more concerned about food additives, or paranoid about the potential health impacts of ultra-processed foods. Most of us grocery shop in a hurry and don’t have PhDs in biochemistry. Closely reading every ingredient list for signs of danger and parsing every nutrition fact panel isn’t practical.

Yuka offers an attractive and user-friendly way of simplifying all the information into a quick and easy takeaway. I think the effort is well-intentioned, but I don’t personally use the Yuka app to vet the products I buy. Here’s why.

First of all, I don’t love the language that Yuka uses to rate products. Each food gets labeled “bad,” “poor,” “good,” or “excellent.” While I firmly believe that some foods are objectively a better nutritional choice than others, I also think that labeling foods with moralizing terms like “bad” and “good” is kind of icky. It encourages a disordered approach to eating, and I find it deeply irritating to be told that Oreos are “bad” and get a 0/100. Sorry, but Oreos are delicious! I deserve a judgment-free Oreo every now and again! Can we find a less snotty way of conveying the fact that they are, in fact, not health food? Maybe this seems like nitpicking, but words matter.

I’ve also come across some inaccuracies with the nutritional information within the app. I first used Yuka when I was researching our kids snack bar buying guide last fall, and found that sometimes the numbers didn’t match what was on the actual product packaging. Some of the food data found on the Yuka app is provided directly by manufacturers, and some is entered by Yuka users. In the former case, information might be incorrect because a product has been reformulated without being updated in the Yuka database. In the latter case, it’s not hard to imagine users making errors when they key in product information. Given how Yuka’s algorithm works — more on that below — a small change in calorie count or the presence or absence of a single additive can be enough to bump it from “good” to “poor.”

But my main gripe with Yuka: As I’ve experimented with the app over a period of months, I’ve found that I simply don’t agree with the ratings it provides and don’t feel confident that it offers trustworthy guidance. Expressing a food’s dietary virtue through a number score creates a false sense of quantitative precision — of objective truth — when these judgments are in fact highly subjective and very sensitive to the particular views of the people behind the algorithm.

For example, let’s look at Siggi’s Vanilla Smoothie, to which Yuka gives a “bad” score (24/100). The product is deemed to have too much sugar per serving (17 grams) and too many calories (150). It also contains pectins, which Yuka classifies as an additive of “limited” concern — yellow light — despite the fact that they are soluble fiber naturally occurring in fruits, and there’s some evidence showing that they have beneficial health effects. According to Yuka’s formula, all this adds up to a bad score.

What doesn’t seem to have been given much (or any) weight in the calculation is that the smoothie is minimally processed, has 9 grams of naturally occurring protein, contains live active cultures — great for the gut microbiome — and that less than half of the sugars inside are added sugars. I often drink this smoothie after running, when the calories and the sugar are needed.

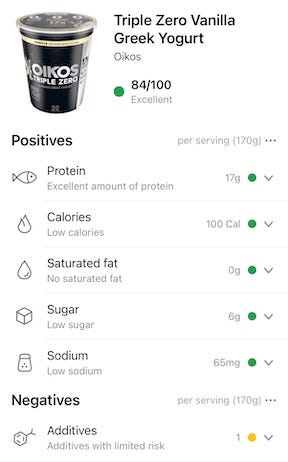

Conversely, the app gives Oikos Triple Zero Nonfat Vanilla Greek Yogurt an “excellent” score (84/100), even though it’s sweetened with the zero-calorie sweetener Stevia. This yogurt is low in calories, fat, and sugar, and high in protein, all rewarded handsomely by the algorithm.

At this point you might be wondering how Yuka makes its scoring decisions. Yuka publishes the components of its scoring algorithm on its website. Here’s the basic breakdown:

60% of the score is based on the nutritional content of food, as calculated by Nutri-Score. Nutri-Score is a scoring system that was developed by public health researchers in France to help consumers quickly understand food quality; it gives products letter grades from A to E, which appear on food packaging in six European countries. You can go deep on Nutri-Score here. But according to a source of mine — a nutritional epidemiologist whose PhD work was on nutrition ratings systems — Nutri-Score is seen by many experts as “pretty outdated in its thinking about nutritional composition of foods,” particularly in giving too much negative weight to fat and calorie content.

30% of the score is based on the presence of additives. Yuka’s team assigns a risk level to each additive based on the recommendations of the EFSA, the IARC, and its own interpretations of the research. I’ll note here that there’s a considerable amount of discretion and scientific literacy involved in this process, and neither of the Yuka team members doing this work holds a PhD.

10% of the score is based on the product’s organic status. While there’s no research basis for the idea that organic foods are more nutritious than conventional, I’m guessing the rationale for this is that organic foods don’t carry the risk of toxic pesticide residue. So, fine.

It all sounds reasonable enough, but now it’s time to get back to those two shopping baskets.

On the left: Cheerios, a Chobani peach Greek yogurt drink, Oatly oat milk, Wheat Thins, Annie’s organic mac and cheese, and Annie’s Organic Cheddar Bunnies.

On the right: Magic Spoon cereal, Goodles vegan mac and cheese, Triscuits, Oikos salted caramel nonfat yogurt with sea salt praline pretzels, dark chocolate and butter toffee, Almond Breeze unsweetened almond milk, and Catalina Crunch Cinnamon Toast cereal.

Any guesses which basket is full of “poor” and “bad” products that you should be frankly ashamed to even be seen with, and which is full of “excellent,” extremely virtuous foodstuffs?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Consumed to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.