It’s Beef Now, Too?

Recalls, outbreaks, and searching for signal in a whole lot of food safety noise

The food safety vibes these days are not good. Late last month, 34 people were hospitalized after eating onions at McDonald’s that were tainted with E. coli. That same week my kids’ favorite brand of breakfast waffles was recalled because of potential listeria contamination. Last Thursday, the bad news came for organic carrots; another outbreak, once again caused by E. coli, followed by yet another warning yesterday about 165,000 pounds of E.coli-tainted ground beef. And on Tuesday, New York Magazine dropped this damning postmortem of Boar’s Head’s blockbuster summer listeria outbreak, which featured stomach-turning descriptions of mixers spraying meat “onto walls and ceilings, where it was left to rot” and “black mold in a room where meat was cured” — images that will now and forever flicker inside my mind’s eye when I bite into a ham sandwich.

When news like this starts to stack up, it can feel like we’re seeing a systemic problem bubble to the surface; that the spate of outbreaks and recalls points to a food system less safe and sanitary than it used to be. Should you be worried? Let’s dive in.

Are food recalls actually on the rise?

Let’s cut right to the chase. No, the number of food recalls is not unusually high.

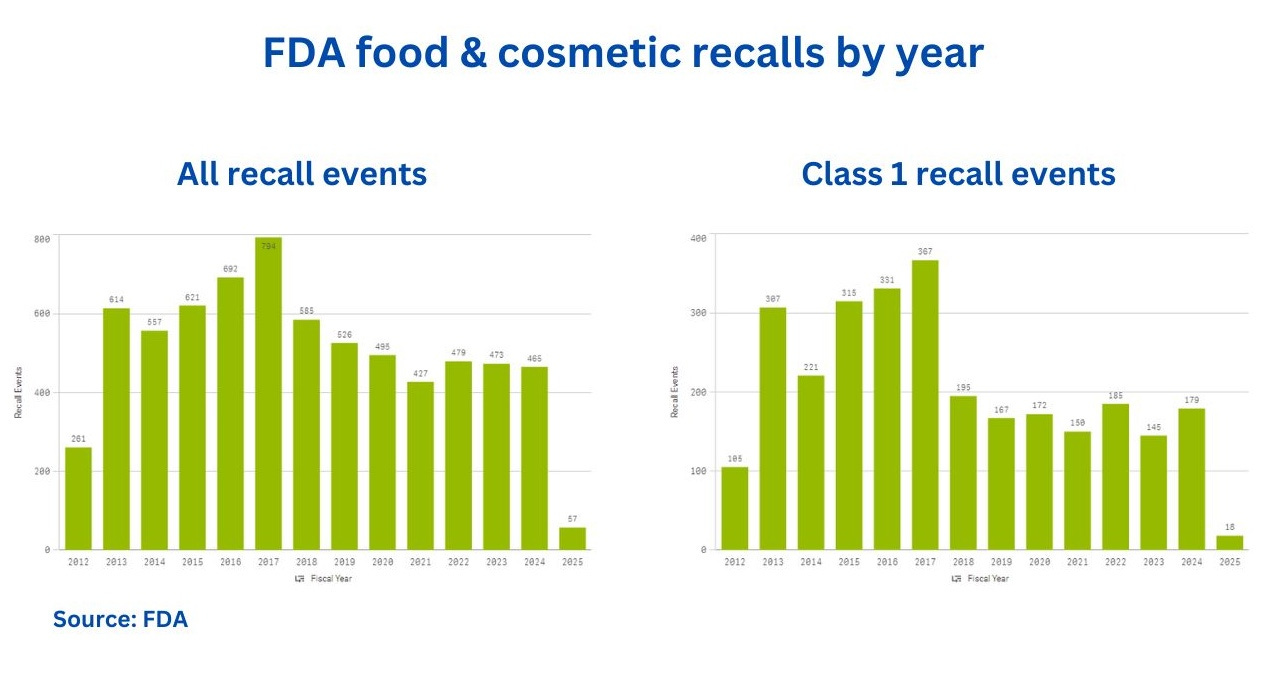

Two federal agencies oversee food recalls: the USDA handles meat, poultry, and some egg products, and the FDA does everything else. As you can see from the graphs below, the number of FDA recalls is actually down slightly over the past seven years, both in terms of recalls overall and Class 1 recalls, which deal with the most serious product issues (the reason why there are recalls already announced for 2025 is not that the FDA is clairvoyant, but rather that recalls are classified not by calendar year, but by the FDA’s fiscal year, which ended September 30th).

The USDA issues fewer recalls per year, on average, and there the numbers are also trending down. This year, the USDA has issued just 31 recalls to date, compared to 124 in 2019.

Another thing you’ll notice in the charts above is just how large these numbers are — 465 recalls, almost 9 every week, in 2024. In other words, while you might only hear about recalls sporadically, they’re happening all the time. They tend to make the news when a big name brand is involved (McDonald’s; Boar’s Head), and/or when there are hospitalizations and deaths that result. (Most recalls are precautionary, and don’t actually result in illnesses.)

There are times — like right now — when food recalls seem to cluster. One explanation for this is that once a big, dramatic food safety event takes place, like the recent Boar’s Head debacle, reporters and editors are more likely to notice and write about additional recalls. After reading about a recall, you’re more likely to notice other stories about them, too (the Baader-Meinhof phenomenon at work). Algorithms that serve you more food safety stories after you read the first one magnify all that. The result is that it feels like the food system is crumbling, even when recalls are at normal levels.

Can you feel a ‘but’ coming?

That’s all reassuring. But: whether recalls and outbreaks are increasing is, I think, the wrong question to be asking. Every year, well over 100,000 people find themselves hospitalized from a food-borne illness, and only a tiny fraction of those cases happen as part of an outbreak.1 A helpful (if very dark!) analogy is the relationship between mass shootings and gun violence overall. While mass shootings get the media attention, and provoke the fear, they don’t account for most of the actual gun fatalities in this country. That’s similar to outbreaks and food-borne illnesses.

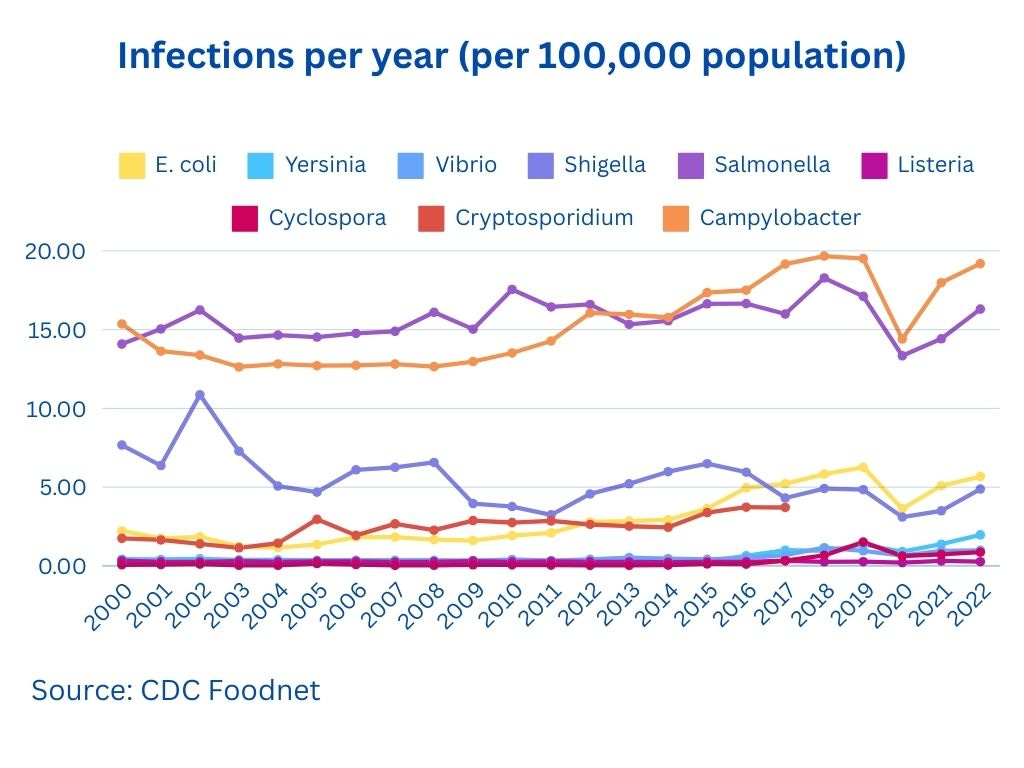

What we really want to understand is how many people are getting sick each year from the food they eat, and how those numbers have changed over time. For that we must turn to the CDC, which tracks all illnesses from major food-borne pathogens nationally.2

You’ll see in the graph below that illnesses due to almost every pathogen tracked either flat or up since 2000 (this graph runs only through 2022, but preliminary data from 2023 shows the same trends). Simply put: more people are getting sick from the food they eat today than a decade or two ago.

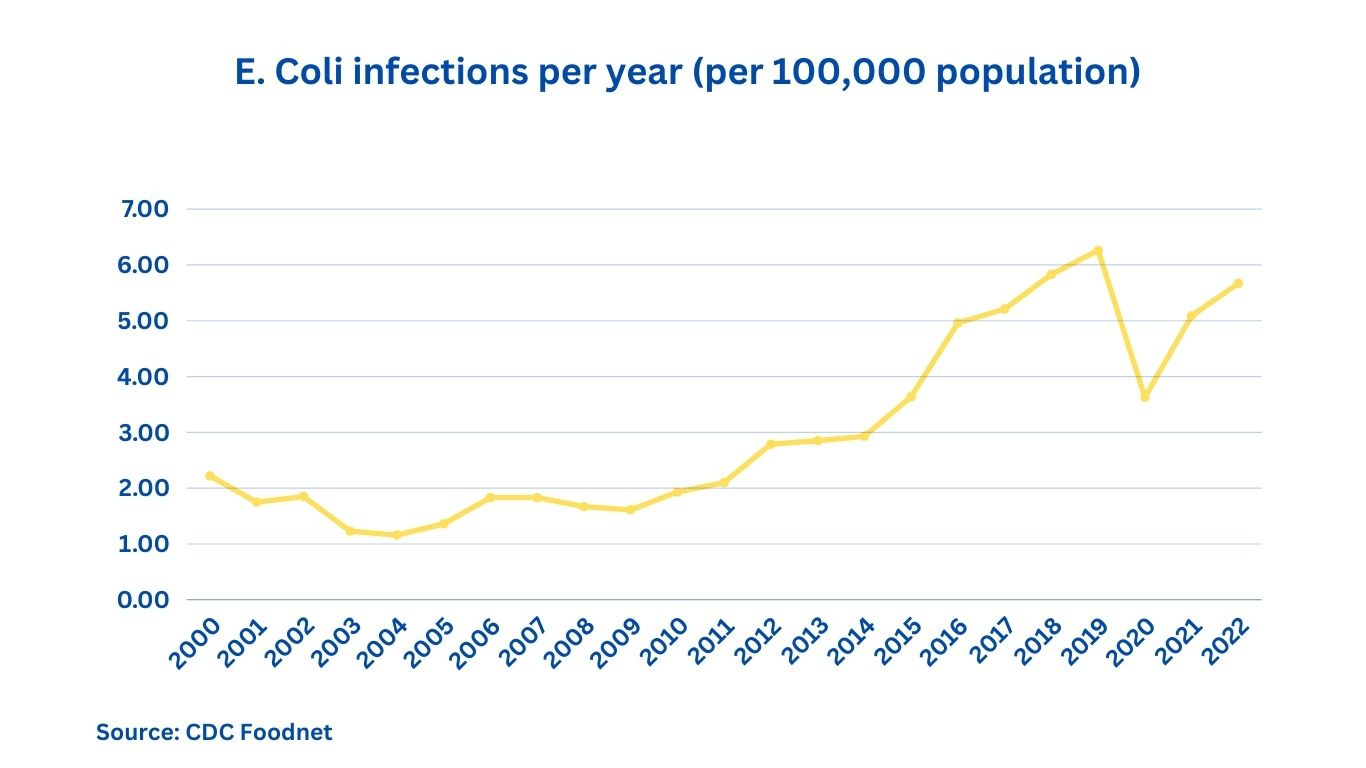

Why might this be? It’s hard to make generalizations across all these bugs, because they get mixed up in the food supply in different ways and for different reasons. So I want to focus specifically on E. coli, because it’s relatively common, particularly dangerous, and cases have been steadily increasing. Here’s the trend line for E. coli infection on its own.

What’s going on with E. coli?

To find out, I called up David Acheson, an infectious disease physician turned senior food safety official at the USDA and then the FDA. Today, Acheson runs a consulting firm that works with the industry on food-borne illness prevention. He’s just about the best person to answer this question.

Acheson believes the increase we see in this CDC data is due, in part, to improved detection and reporting of E. coli illness. But that’s not the whole story. “I do think there’s a genuine increase in cases,” Acheson told me. While there’s no smoking gun evidence that explains why E. coli is on the rise, Acheson’s view — which is commonly held among food safety experts — is that fecal contamination of vegetable fields is a major explanation for the increase.

E. coli lives in the intestines of cows, and it’s shed in their manure. Much of our vegetable production in the United States, in places like California and Arizona, is located in close proximity to large cattle operations. The theory is that in these locations, manure is drifting into contact with lettuces, spinach, and yes, organic carrots. “It might be airborne on a dry day,” Acheson said. “It could be transported by feral animals, or moving around in the water supply.” Why the problem has worsened over the past decade is another question mark: “Are the cows less healthy? It’s been hotter and dryer, so is there more airborne fecal matter? We don’t really know.”

Produce growers and processors have gone to great lengths to put safeguards in place so that E. coli stays out of the food supply; when it slips through, it does so at random. There simply isn’t much you can do as a consumer to protect yourself from getting a dodgy spinach leaf on your salad, or infectious onions at a fast food chain.

“There are things you have control over, and there are things you don’t,” Acheson said. We’ve been talking so far about the rise in E. coli contaminating produce at the source, but a substantial portion of E. coli cases today (as in the past) result from people mishandling raw meat at home. Acheson recommends focusing on that part of the problem. “Cook your meat fully,” he said. “Don’t cross-contaminate surfaces.” You can cut down on your overall risk by following those guidelines.

The bottom line: Don’t get rattled when there’s a string of recalls or outbreaks in the news. But do understand that the number of food-borne illness infections — E. coli infections in particular — is on the rise. And while you can’t totally eliminate your risk of getting sick from what you eat, being extra careful when handling raw meat will help reduce it.

The definition of an ‘outbreak’ is when two or more people experience the same illness after eating the same food.

When a person tests positive for one of these bugs, the doctor or hospital is required to report it to the CDC. This means we have a pretty clear picture here of how illnesses are trending.