The Ribeye Revolution: Inside MAHA's Protein-Packed Dietary Guidelines

RFK Jr. says that new nutrition advice is a historic reset. We fact-checked his claims—and found a steak-sized contradiction at the heart of his dietary overhaul

Hello nutrition nerds! On Wednesday, the Trump administration unveiled the 2025 Dietary Guidelines for Americans, the federal nutrition advice that guides meals served in the military, school lunches, as well as the broader public understanding of how to eat for health. The guidelines, which come out every five years (and are a tad late this time around), have been hailed by the Make America Healthy Again (MAHA) movement as a centerpiece of its radical agenda.

At a White House press conference, Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. declared that the new guidelines served up “decisive change,” and called them the “most significant reset of federal nutrition policy in history.” He added that they “replace corporate-driven assumptions with common sense goals and gold-standard scientific integrity.”

It might have been snappier to just call it Nutrition Liberation Day.

It’s not exactly news that Kennedy and his MAHA acolytes are prone to hyperbole. So let’s take a look at what’s in this year’s guidelines — and factcheck Kennedy’s claims.

Decisive Change (True-ish)

Kennedy’s claim of revolution is based on the guidelines focus on “whole, nutrient-dense” foods and its novel warning against “highly processed” foods1, which make up more than 50 percent of the American diet.

In fact, the guidelines have always emphasized whole foods. And though they haven’t directly warned against processed foods, they have targeted refined carbohydrates, added sugar, and sodium, which are nutrition speak for Fritos and Pop-Tarts.

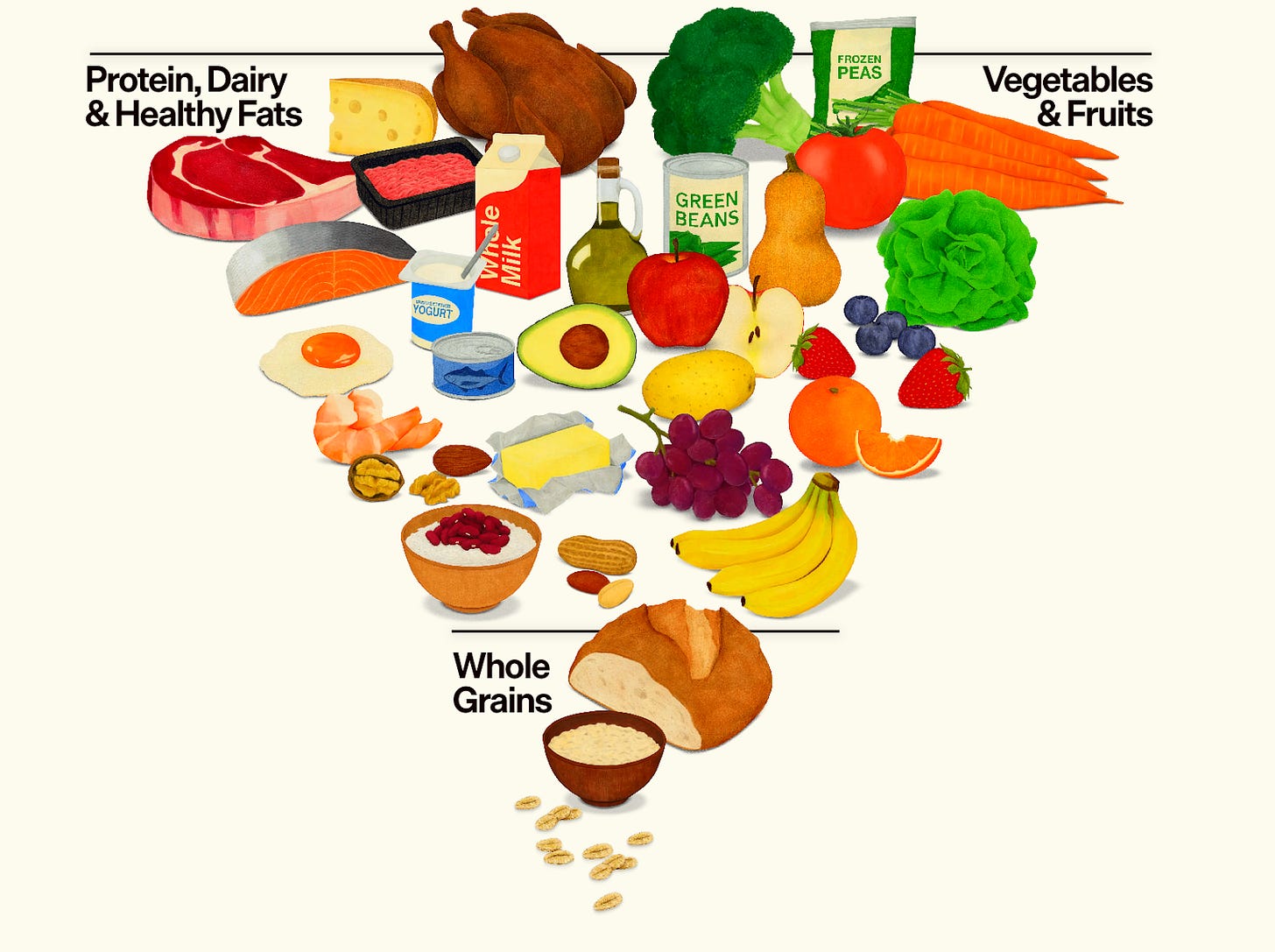

The decisive change came in the new food pyramid, which literally flips the old one on its head. Now even whole grains are minimized, and steak, cheese, whole milk, plus fruits and vegetables, are at the top. To justify this flip, the new guidelines reject more than half of the recommendations provided by the official Dietary Guidelines Advisory Council, an independent group of scientists that spent two years reviewing “gold-standard” research to make recommendations. (Yikes!)2

If there’s anything I like about this year’s guidelines, it’s that they are easier for the average consumer to understand than previous iterations. There is a bold, splashy website that feels like a Hollywood movie trailer: “America is sick…The data is clear.” (Cue scary music.)

And the overview, at just seven pages, includes simple, actionable advice like “pay attention to portion sizes” (which is, to my mind, the single most important piece of dietary advice) and “100% fruit or vegetable juice should be consumed in limited portions or diluted with water” (also good advice). The guidelines even offer an uncharacteristically restrained take on the microbiome, suggesting that “vegetables, fruits, fermented foods (e.g., sauerkraut, kimchi, kefir, miso), and high-fiber foods support a diverse microbiome, which may be beneficial for health.”

Given that one of the most long-standing critiques of the dietary guidelines is that no one actually follows them, presenting them in plain English is a step in the right direction. If only all that clear advice were good…

“The Most Significant Reset of Federal Nutrition Policy in History” (True – but not in a good way)

The scuttlebutt in the run-up to the big reveal was that Kennedy planned to reverse the guidelines’ recommended limit on saturated fats, which dates back to 1990. The move is considered heretical by the nutrition elite, who almost unanimously agree that limiting saturated fat is beneficial to health, especially for preventing cardiovascular disease, which remains the number-one cause of death in the U.S.

But it seems not even MAHA was brazen enough to officially change America’s one truly solid piece of good nutrition advice: The guidelines left unchanged that saturated fat should not exceed 10% of total daily calories.

Though it might as well have. In a direct challenge to the nutrition establishment, the guidelines also recommend that Americans prioritize protein at every meal, increasing their intake by 50 to 100%.3 Moreover, the guidelines counsel Americans to prioritize animal protein, including eggs, poultry, seafood, and red meat. (Yes, that’s a ribeye at the top of the food pyramid!) Plant protein, including beans, peas, lentils etc., are characterized as complementary to a healthy diet. Given the clear, consistent association between high levels of red meat consumption and negative health outcomes, such as colorectal cancer, cardiovascular disease, Type-2 diabetes, and all-cause mortality, the new guidance is a real headscratcher.

Or is it? Because just like that, MAHA skirted the inevitable blowback of changing the cap on saturated fat, while simultaneously undermining the suggested limit. This is how Kennedy “ends the war on saturated fats.” As The New York Times noted, consuming one eight-ounce ribeye would put many people over their daily saturated fat limit.

The guidelines’ “war on added sugar” also set up another impossible-to-meet threshold. Previous guidance had recommended that added sugars be limited to 10% of daily calories, so 50 grams per day in a 2,000 calorie diet, a level which less than half of Americans manage to meet. Now, the guidelines counsel that, “while no amount of added sugars or non-nutritive sweeteners is recommended or considered part of a healthy or nutritious diet, one meal should contain no more than 10 grams of added sugars.” If we assume that people still eat only three meals a day, that means the limit is just 30 grams — or just one cup of the seemingly harmless Starbucks honey-mint tea daily. To the horror of guilty parents everywhere, the guidelines also recommend that children under 10 eat no added sugars in their diet. Kennedy may go down in history as the Grinch who stole Christmas (and Halloween, Valentine’s Day, birthdays, and more.)

“Replace Corporate-Driven Assumptions with Common-Sense Goals and Gold-Standard Scientific Integrity” (False)

MAHA embraces a hornet’s nest of conspiracy theories: Corrupt regulators. Drug companies conniving to make people sick and profit off them. And, when it comes to nutrition, a cabal of elite scientists who quashed the evidence that saturated fat was, in fact, good for us: “For decades, Americans have been fed a corrupt food pyramid that focused on demonizing natural saturated fat,” FDA Commissioner Marty Makary said at the press conference. He called the new guidelines the “beginning of the end of medical dogma on nutrition.”

This theory has been floating around for years, promoted most vociferously by Nina Teicholz, a nutrition crusader and author of the 2014 book, The Big Fat Surprise: Why Butter, Meat, and Cheese Belong in a Healthy Diet. (You can read more about the book in a story I wrote in Elle.) The short version of her thesis is that the consensus that saturated fat is bad comes from weak, observational studies, rather than “gold-standard,” randomized-control studies. She accuses leading nutritionists of bias and cherry-picked data.

But MAHA’s embrace of saturated fat is itself a study in cherry-picked data. A case in point: One of Teicholz’s key examples of excluded data is the 1989 Minnesota Coronary Survey, which she says showed that men and women eating a diet of 18 percent saturated fat had no more “cardiovascular events, cardiovascular deaths or total mortality” than those eating a diet with 9 percent saturated fat.

In fact, the study was a failed trial based on institutionalized patients in mental hospitals. It did not meet its enrollment goals and did not track the patients for the time required (as many were released before it was completed). Walter Willett, a professor of Epidemiology and Nutrition at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, told me the study is “basically uninformative and useless.”

In a world where nutrition science changes every day — red wine is good for you! Oh, wait, never mind! — the consensus on limiting saturated fat has remained remarkably consistent. One member of the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee, the group of experts who spent two years preparing a report on the most up-to-date nutrition research to guide policymakers — told me that the science on saturated fat is so solid that there was “no reason to relitigate it …The science is there.”

In other words, nutrition science in the MAHA age is just as political — and arguably more so — than ever.

What do you think of the new guidelines? Will you try to follow them? (Did you ever follow them?

POSTSCRIPT: In the first (and probably) last time I ever follow White House Press Secretary Karoline Leavitt’s advice, I decided, after the Wednesday press conference, to eat a salad for lunch. It was unintentionally a model of the new dietary guidelines — chicken, avocado, beets, squash, cucumbers, olive oil, etc. But then, while writing this piece, I went downstairs to sneak a piece of (delicious) chocolate cake that my daughter made this weekend. Change is hard.

The administration chose to steer clear of the term “ultra-processed foods” as it does not yet have a formal federal definition.

The Internet hive mind suggests that the science used to elevate of beef and dairy comes from studies funded by the beef and dairy industries. I have not yet been able to go through the full list of studies. But, if true, so much for “gold-standard” science.

The Scientific Foundation for the Dietary Guidelines, a 90-page document in support of the overview, justifies the change, arguing that “the current Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) for protein—0.8 grams per kilogram of body weight per day—was established to prevent protein deficiency … but does not reflect the intake required to maintain optimal muscle mass or metabolic function under all conditions.” It is certainly true that there are studies that support this. But there isn’t a scientific consensus, which is what the dietary guidelines are supposed to represent.

bravo on the cake (and the post as well) - i hope it tasted as good as imagined it would

The new guidelines engender a personal phenomenon I am struggling with in this administration. I find it necessary to bring a healthy level of skepticism to anything produced from this administration, including sources I previously trusted without much question, such as the CDC. The skepticism and the checking are exhausting and time consuming. I then find that I land somewhere that I am recognizing nuggets of “good” information / recommendations / etc., while dismissing some I deem unscientific or non-evidence based. And then I wonder if I am cherry picking myself to support my current world view?!

These guidelines are no different. I eat meat very rarely for health and environmental reasons, so I am dismissive of the renewed focus on meat-based protein because I feel like the science does not support it. I have tried with only modest success to limit my son’s added sugar consumption, so I pplaud the outright focus on that, even with unrealistic guidelines for children. So….I guess I will follow these guidelines to the extent they match what I’m already doing, because I have attempted to model my behavior on past science and evidence?! Or am I just hearing what I want to hear?!?! 🤪